From the sparkling Manhattan skyline to the most flood-prone basement in Queens, New York City is powered almost entirely by fossil gas—and the huge gas-fueled “peaker” plants that spin up at times of peak electricity demand are polluting New York’s poorest neighborhoods. Scientists can measure a neighborhood’s air pollution and predict how many people will die prematurely from it each year.

The main reason New York City’s grid is so dirty isn’t that there’s no clean power to be had. It’s that there’s no way to plug into it. For decades, transmission bottlenecks have kept New York City in a silo of dirty gas power, mostly cut off from the cleaner statewide grid. Until last year, the city had only one significant source of non-fossil power: the Indian Point nuclear power plant on the shore of the Hudson. Now, with Indian Point shut down, it has none.

That’s about to change. On Thursday, April 14, the state Public Service Commission voted 5-2 to advance two large transmission projects under a program known as Tier 4, designed to allow the city to purchase large amounts of renewable power. Together, the two projects are projected to reduce New York City’s use of fossil fuel power by more than 50 percent over the next decade.

Some of New York’s climate and environment advocates are celebrating. Others are fuming. It’s a mess—and at the heart of it is the Champlain Hudson Power Express, a controversial project that might just be necessary for New York State to meet the targets of its own climate law.

Getting CHPE

One of the Tier 4 projects, an underground transmission line called Clean Path, is slated to carry New York wind, solar, and hydropower into the city from the edge of Delaware County under existing transmission right-of-ways. Like anything built anywhere, Clean Path has opponents, but has been relatively uncontroversial among New York climate organizations.

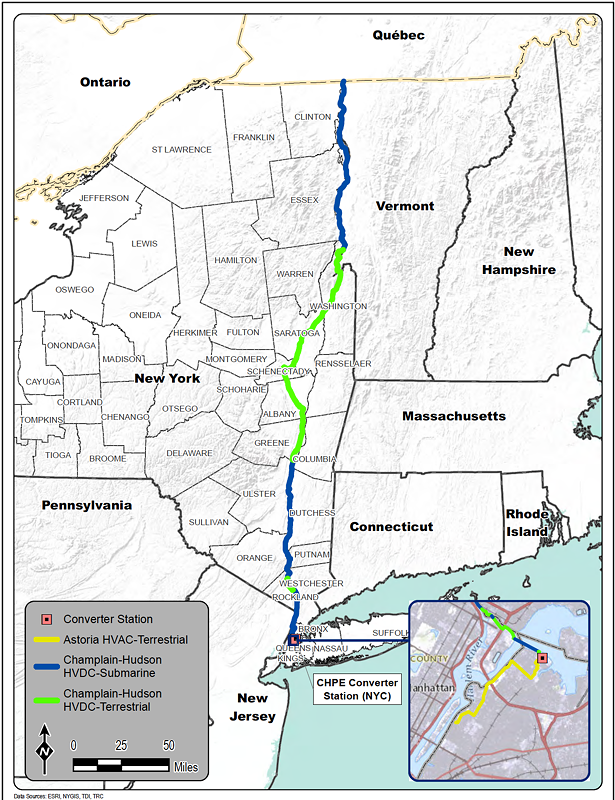

The other project is a 339-mile power cable planned to run under the Hudson River to Hydro-Quebec-owned hydropower sources in Canada, known as CHPE (pronounced “chippy”). CHPE has been in the works for more than a decade. The National Resources Defense Council is for it. The Sierra Club is against it. In the Hudson Valley, it has drawn intense opposition from a small but vocal alliance of environment and climate advocates. Recent opposition has been fiercest from one of the project’s former supporters: the influential environmental organization Riverkeeper.

As HuffPost reporter Alex Kaufman writes in a long feature on the controversy around CHPE, the project has all its permits in place, and its backers, Hydro-Quebec and the Blackstone Group, are ready to start construction almost immediately. But if it is derailed, it could take years for an alternate project to work its way through the approval process and start delivering power—and because the agreement for New York City’s CHPE power purchases was signed before large recent spikes in the cost of electricity, that power would be more expensive.

At the heart of most environmentalists’ objections to CHPE are the impacts of dams on the environment, and on Indigenous communities living near them. The environmental costs of hydropower are real, as is the deep history of land theft and injustice by dam-builders against Indigenous communities in Canada and elsewhere. But it is hard to make a case on the scientific evidence that CHPE won’t reduce the New York City power sector’s massive climate footprint, and even harder to argue that it won’t save lives in New York City’s most pollution-plagued environmental justice communities.

In Thursday’s PSC session, the arguments made by Riverkeeper and other environmentalist opponents of CHPE were little to be heard. In comments explaining their votes, the two commissioners who voted against the Tier 4 projects, John Howard and Diane Burman, mostly leaned on arguments made by fossil fuel interests and utilities that are generally fighting efforts to meet the goals of New York’s climate law, the 2019 Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA), and cited worries that putting New York’s climate law into action would be costly to ratepayers.

“The Commission must balance the CLCPA with other obligations,” Burman said, arguing that efforts to meet climate goals would impose “unsustainable” costs on utility ratepayers, a burden that would fall hard on upstate businesses while the benefits of Tier 4 disproportionately flowed to New York City. Advocates for the effort to meet the CLCPA’s ambitious emissions targets “need to examine their magical thinking,” she added.

The Perils of Damnation

When a river is dammed to create a reservoir, decaying vegetation releases methane, a potent greenhouse gas. It also releases methyl mercury, a pervasive environmental contaminant produced by coal-burning that builds up in the fat of fish behind the dam and makes them toxic to the Indigenous communities that rely on them for food. Both methane and methyl mercury are released immediately in the wake of the dam’s construction; while methane emissions decline quickly once the dam is established, methyl mercury can keep accumulating for decades in the food web, as the reservoir shifts from a rotting underwater ex-forest to a more stable lake-like ecosystem.

Project opponents sometimes claim that hydropower is “worse than coal” for climate, or argue that the greenhouse gas emissions caused by methane from dying vegetation under a dam site are on par with fossil fuel burning. Methane from dams is indeed a problem, especially from newly constructed dams where a lot of decomposition is happening, and one that policymakers have been guilty of underestimating. But the idea that power from a typical hydropower reservoir over its lifetime—especially one in a cold northern climate—is on par with coal- or natural gas-fired power, climate-wise, doesn’t hold up to scientific scrutiny.

Power for New York City through CHPE won’t come from new dams. The program’s rules, which are aimed at encouraging the buildout of new non-hydro renewables like wind and solar, require that all hydropower sold under Tier 4 must come from dams that were already under construction by June 18, 2020. But opponents fear that the sale of power to New York will free Hydro-Quebec to build new dams to serve other customers.

“The agreement with New York City explicitly says that this contract will not lead to any new impoundments in Quebec,” said Ben Furnas, formerly the head of New York City’s sustainability efforts under Mayor Bill de Blasio, who now heads up an ambitious climate research and solutions project at Cornell University.

Canadian project opponents have heard promises before, and are wary.

“We believe they’ll have to build new dams,” said Roberta Benefiel, a water protector in Happy Valley-Goose Bay who volunteers as Grand Labrador Riverkeeper, speaking at a press conference held by Riverkeeper to showcase the voices of Indigenous opponents to the project.

William Nicholls, a Cree dam opponent from Mistissini, said that Hydro-Quebec was under increasing pressure to sell power outside of Canada, and is already urging local customers to reduce power use.

“Where are they going to get it from? Of course they’re going to come back to native lands,” he said.

Switching Sides

On Tuesday, two days ahead of the PSC’s crucial vote, a prominent New York City community-oriented climate organization decided that CHPE wasn’t perfect, but it would have to be good enough. New York Communities for Change, a group that led in the successful effort to pass a citywide “gas ban” on fossil fuels in new construction and emissions caps on large buildings, announced in a brief statement that its members had voted to reverse course and throw their support behind CHPE.

“For years, NYCC opposed the Champlain Hudson Power Express (CHPE). We believe there could have been better alternatives, including fully public projects,” the statement reads. “However, due to the state’s failings, New York now faces a very limited decision: CHPE is the only project that can be built on a relatively short timeline and go into service in 2025.”

In its bluntness, NYCC’s statement addresses a brutal fact of climate realpolitik: New York is running out of time, and so is the world. In climate time, delay is as destructive as denial. “The UN has told us it is ‘now or never,’” NYCC wrote. “There is simply no time left to waste to bring renewable energy to New York City.”

A devastating recent report from the United Nations’ IPCC stated clearly that global emissions must peak and begin to decline by 2025 in order to keep planetary warming to a more livable 1.5 degrees Celsius, and stave off the worst futures. For New York, the Tier 4 program is critical to meeting the state climate law’s deadline of sourcing 70 percent of the state’s electrical power from renewables by 2030.

“Much respect for the good faith opposition but we feel like at this point it needs to be approved. No time left!” Pete Sikora, NYCC’s climate campaign director, wrote on Twitter.

Tier 4 is also key to New York City's local law regulating building emissions—and it’s creating some strange bedfellows. Because they need to be able to purchase clean power to abide by the city’s Local Law 97, which limits emissions from large buildings, large city real estate interests are lining up behind the CHPE.

The other Tier 4 project approved by the PSC, the underground Clean Path, will eventually help light up the New York skyline also. But even if it were built today, Clean Path would be an extension cord without a full power source. It will carry hydropower into the city from the New York Power Authority’s Blenheim-Gilboa Pumped Storage facility, built in 1973, but many of the homegrown upstate wind and solar projects that will power Clean Path are not yet operational, and won’t be available by the time Local Law 97 emissions caps begin in 2024.

NYCC isn’t the only prominent New York climate organization that has switched sides. Riverkeeper, one of the Hudson Valley’s oldest and most powerful environmental organizations, has led the charge against CHPE in the past year, building coalitions with Indigenous groups opposed to the project and towns that rely on the Hudson for drinking water in an effort to shut down the project. But in 2012, Riverkeeper, along with Scenic Hudson and Trout Unlimited, signed off on a statement of support for CHPE, in a joint settlement with other stakeholders that put all three environmental organizations on the board of a $117 million trust fund established to address any environmental issues that might arise during project construction.

Riverkeeper’s flip-flop on the issue has been a source of frustration for pro-CHPE climate advocates, who often point out that the group began fighting CHPE in earnest only after winning a shutdown of the Indian Point nuclear power plant.

“We’re willing to admit we didn’t get the facts right the first time,” said Riverkeeper president Tracy Brown. “It’s frustrating to be painted now as somehow a villain because we’re learning and listening and responding to the conditions on the ground.”

For its part, Riverkeeper maintains that there are better proposed projects that could be included in the Tier 4 program instead of CHPE, but declines to specify which ones.

“Riverkeeper is a water protector. We’re not an energy organization,” Brown said. “I’m not here to shill for any one energy entity over another, but there are projects under consideration that include solar and wind in New York State.”

Hearing Indigenous Voices

Not all of Canada’s First Nations are opposed to CHPE, and the responses to the project are as varied as the Indigenous nations in Hydro-Quebec’s territory themselves.

One prominent Indigenous leader—Kahsennenhawe Sky-Deer, recently elected chief of the Kahnawàke Mohawk, and the community’s first female and LGBTQ-identified leader—is working in partnership with the project on her community’s lands, and has urged support of CHPE. Kahnawàke ironworkers were instrumental in building New York City’s tallest skyscrapers more than a century ago, and Sky-Deer sees this project as in line with a long relationship between city infrastructure and her people.

“Too often in the past, infrastructure projects have been imposed on communities whose concerns were not listened to, including Indigenous communities,” she writes, in an op-ed for the Rockland/Westchester Journal News co-written with several New York supporters. “This project represents a turning point, where not only have such concerns been listened to, but the Mohawk Council of Kahnawàke in Canada is actually a partner in this transmission project that will be located on its traditional territory. That partnership will bring real benefits to the community.”

At Riverkeeper’s press conference, project opponent Lucien Wabanonik, councilor of Lac Simon Anishinaabe Nation, urged all parties involved to engage seriously with Indigenous opponents to the project, and to work with them to restore injustices and prevent future harm to Canadian First Nations communities. “If they start talking seriously with us, we might find options for solutions,” he said. “There are things we cannot change. We will not be talking about taking away the dams and power lines that are already on the lands of our people. The damage is already so big.”

In 2019, members of the de Blasio administration spent two weeks touring Inuit, Cree, and Innu territory to meet with Indigenous leaders on their concerns about the power purchase agreement with Hydro-Quebec. “We wanted to make sure that nothing we do will make life worse for anyone in this project,” Furnas said.

Climate Advocates React

While CHPE has now cleared the last state hurdle to begin construction, there’s still the potential that one of the larger environmental organizations, or some other opponent with deep pockets, might sue in an effort to prevent the project from getting underway. “Until the electricity is actually flowing down to constructed lines, I won’t exhale,” Furnas said.

Daniel Zarrilli, a former climate advisor to de Blasio who is now a climate policy advisor to Columbia University, was a little more celebratory in the wake of the PSC’s vote. “This is just a transformative moment for New York City to be able to see what the pathway actually looks like to decarbonization. It’s not the only thing that needs to happen in New York City, but it’s a critical piece of the puzzle.”

Local climate advocates are less enthusiastic. Sarahana Shrestha, a climate organizer who has been a staunch opponent of CHPE, wrote on Twitter of her frustration at the PSC’s Thursday decision. “CHPE has been a source of immense frustration to organizers in the Hudson Valley, and the way in which we have arrived at this outcome is a clear illustration of why we need real climate leadership.”

Shrestha, who is challenging longtime Hudson Valley representative Kevin Cahill in the upcoming Democratic primary in Assembly District 103, has built a campaign around climate action and Cahill’s reluctance to push for legislation that would make CLCPA goals a reality. Shrestha is pushing hard for a bill that would free the New York Power Authority to build more renewable power on New York soil, the Build Public Renewables Act.

In explaining her “yes” vote at Thursday’s PSC meeting, commissioner Tracey Edwards might have spoken for the climate movement writ large—or at least, the part of it that is determined not to let the perfect be the enemy of the good.

“We’re running out of time,” she said. “If we analyze everything ‘til it gets 100 percent right, we’re not going to be able to move forward.”

Note: A previous version of this story cited Tier 4 as important to NYC's gas ban in new construction. It's more critical to Local Law 97, another climate-oriented recent city law that caps emissions from large buildings. The story has been corrected.