This article was originally published in the September 2005 issue of Chronogram.

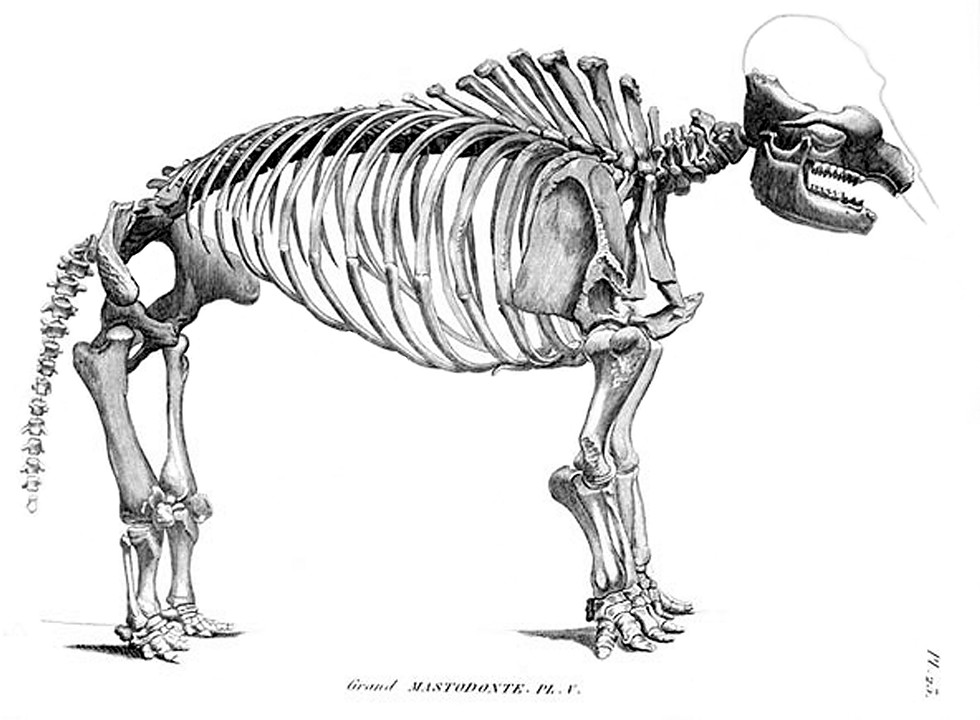

In 1801 on a small farm in the present-day Orange County town of Montgomery, a team set out to exhume the large bones of an animal no human had ever seen. Upon the discovery of a huge thigh bone in 1799 (18 inches in circumference at its narrowest part), rumors spread about the possibility of carnivorous monsters, capable of crushing deer and elk in their “monstrous grinders,” roaming the mostly unexplored American continent.

Finally in 1801, the American Philosophical Society of Philadelphia sponsored the hunt for bones by authorizing portraitist and polymath Charles Wilson Peale to spend the princely sum of $500 on the project. Peale used these funds to lead a team of local laborers in digging up the skeleton of the unknown beast, which had been a popular topic of speculation and debate among Americans since the discovery of the hipbone in 1799. Peale also had assistance from the US Army and Navy, as President Jefferson had a keen interest in the project, hoping to make a discovery to impress Europe.

When workers completed the excavation (which was known as the First US Scientific Expedition) two nearly complete mastodon skeletons were unearthed. “It gave the world a look at the first prehistoric creature,” says Joseph Devine, a local historian. “People would jam Peale’s museum [in Philadelphia] to look at these skeletons. You could walk up and touch it and marvel.”

The mastodon (as it came to be named) soon became a symbol of national pride. Explains Paul Semonin in his book, American Monster: How the Nation’s First Prehistoric Creature Became a Symbol of National Identity (2000), “The great beast had become a symbol of the new nations own conquering spirit, an emblem of overwhelming power in a psychologically insecure society.” Though America enjoys global hegemony at present, it was only 200 years ago that the US had virtually no stature in worldwide society. In the period following the Revolutionary War, many Europeans tried to portray America as a land not worth fighting for. A popular European myth was that a good team of British horses would lose muscle mass and height after only a few years in America. Stories like these contributed to a global anti-Americanism as well as a wounded national pride in a young, struggling nation.

The fascination with mastodons was of particular importance to our founding fathers. In fact, George Washington had made a trip to Montgomery in 1783 to view some preliminary finding of the bones before a complete skeleton was exhumed. (A fist-sized mastodon tooth—believed at first to be evidence of human giants—was unearthed in 1705. In fact, many mastodon discoveries were made throughout the region surrounding Montgomery by accident, mostly due to “farmers digging the muck out of the swamps for fertilizer,” according to Devine.)

When the Montgomery Mastodon was completely unearthed in 1801, President Jefferson used this as a bragging point about how these massive beasts existed in America, but not in Europe. At the time, extinction was not an accepted theory, so many thought more mastodons would be found out west. After the Louisiana Purchase, President Jefferson commanded that explorers Lewis and Clark: “Go west and find mastodons, dead or alive.”

Though the only mastodons found were skeletons, the US was soon swept with mastodon fever. One example of mastodon enthusiasm was an honorary “Mammoth Cheese” made for President Jefferson. The ladies of Cheshire, Massachusetts, gave Jefferson and his guests a unique snack—a single block of cheese that was four feet in diameter, 18 inches tall, and 1,200 pounds. The woman of the small farming community produced the cheese from the single milking of 900 cows, a huge sacrifice for such a small town. It was meant to honor the exhuming of the mastodon, which at the time was known as a mammoth.

Besides bonding Americans through their love of all that is big, the mastodon played a significant role in scientific history; it yielded the first credible statements regarding extinction. Before the mastodon was discovered, the commonly accepted belief was that extinction was impossible, because of the deeply religious beliefs that pervaded throughout America. The idea that one of God’s creatures could have disappeared from the earth was considered ludicrous, as well as blasphemous. The mastodon’s discovery was made at a time when dinosaurs had not yet been discovered and even educated people where not aware of the existence of prehistoric nature.