If you walk north from Broadway in Newburgh up the quieter side of Liberty Street, you’ll reach a spot where the bluestone pavers bulge over the roots of a Norwegian Maple—the largest tree on the block. Under its canopy, there’s a 19th-century, three-story rowhouse with a storefront, number 188.

The storefront has always had a clandestine mystique. About 15 years ago, I walked by often after delivering my social work clients to the substance abuse clinic a few doors down, always slowing my stroll to check it out. A sunburst was carved or painted above the door; it seemed like a pagan calling card. Dark curtains covered the long windows, so, peering in, all I could see was my reflection and the tree swaying behind me. I was new in town, and I suspected I might find my people there—later, I heard a rumor that it was a lair for an anarchist collective—but I never encountered anyone, just rotting leaves gathered at the threshold of a locked door.

Then, after 10 years away from the neighborhood, I was invited in.

On a Saturday afternoon in late September 2019, I was grilling a large paella at a farmers market nearby (I had been writing about food for a few years at that point and was just beginning to cook for small events) when a restaurateur named Sisha Ortuzar came by for a plate and told me I should meet him at a place called Lodger at 188 Liberty Street. “It’s not a restaurant, exactly. You’ll see,” he said.

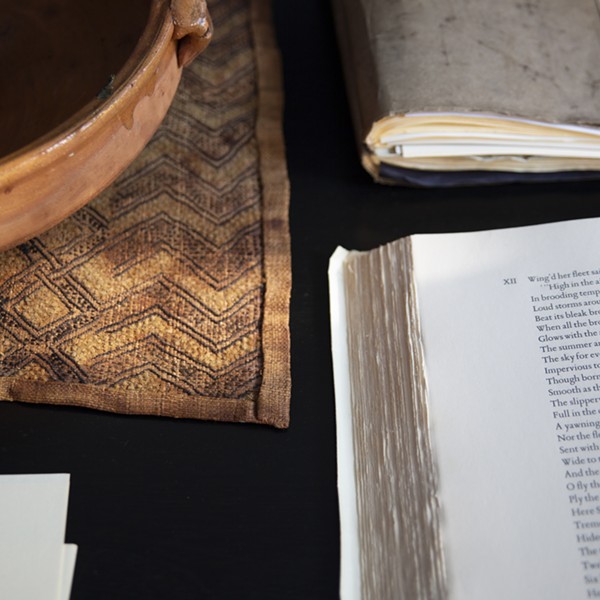

When I arrived that evening, the sunburst on the door was gone; two canvases, each decorated with medieval Italian paintings of blue root vegetables, had replaced the dark window curtains, and the threshold had been swept clean. Squeezing the thumb latch, the door opened, and an aroma of curry and warm North African spices bloomed. Around the small studio's perimeter, Faustian sculptures, crystal shrines, and antique books sat on shelves; brass light fixtures hung on the monochrome cobalt blue walls; vases of flowers, dead and alive, and terracotta bowls filled with potatoes and long-stemmed garlic, sat on antique tapestries draped over long tables.

The front table was perpendicular to the door, blocking the path. A small group sat there quietly over soup bowls, barely clinking silverware as they ate. I locked eyes with a skinny man with a large mustache I vaguely recognized. I wasn’t sure if I had just interrupted some private anarchist meeting, so I explained, “I’m supposed to be meeting Sisha here.” No one responded. As the awkwardness became unbearable, Ortuzar arrived and led me around the table to a kitchen in the back. It was smaller than a home kitchen, with only a small range and a refrigerator. The chef, a big guy dressed all in black with a full gray beard and hair, was crouched before the open oven door, trying to cram a brick underneath one of the racks to keep it from falling over. He stood, looked at us, and then boomed at Ortuzar in a South African accent, “Not a good time, mate!” He lifted the lid on a pot of curried chicken, tasted a spoonful, and then walked to the front to charm the guests. The patrons became loud and cheerful in short order.

Ortuzar and I moved to the backyard and sat at a bistro table. I told him that I was always curious about the place. The inside was like nothing I could have imagined, but also, somehow, fit what I expected. I was surprised when he said it had only been open for a year.

He told me all about it: The irascible and gregarious man we’d just met was Ortuzar’s good friend Leon Johnson. He was an artist and retired art professor who had moved to town from South Africa by way of San Francisco, Oregon, and, most recently, Detroit. This space, Lodger, wasn’t a restaurant but a cauldron where Johnson and his wife Audra Wolowiec (a sound artist and sculptor) could meld creative interests, often in collaboration with their neighbors. At times, it functioned as a gallery, a print shop, a book bindery, a soup kitchen, a community center, a business incubator, a film house, and a workshop for local teens. No matter what was happening, Johnson and his team of two or three local high school kids always served dinner on Fridays and Saturdays at 7pm: usually, a curry or tagine, along with Medjool date bread and hummus. Ortuzar said, “I think he’ll let you cook your paella here. I told him about you.”

It was hard to believe, but Ortuzar was right. Johnson let me, still a novice cook, take over Friday nights once a month for wood-fired paella and live flamenco music in the candlelit front studio; it was an idea I’d envisioned 10 years prior, and Lodger helped me bring it to life with no overhead costs.

Those nights, like every night at Lodger, were intimate and boisterous. Throughout the dinner service, we drank from an endless stream of wine bottles that customers and friends sent back to the line; we peered through the kitchen curtain as the musicians performed and sang with patrons as they came back to join us for an injection of energy and excitement. As guests petered out at the end of the night, unfailingly, some hung behind to meet at the long table in the backyard. We’d collect all the candles and leftover wine bottles from inside and gather there, sometimes while listening to the night's most intimate guitar and singing. On one of those nights, I shared a hand-rolled cigarette with Johnson’s son Marlowe, who is a bartender in Detroit. He said, “My dad just creates this wherever he goes. It’s like his traveling circus.”

It wasn’t just me he let in. When Johnson cleared that threshold, he helped countless people. Local potters and carpenters showcased their work in the space, a Japanese chef tested out her pop-up concept there, and a local Newburgh cook named Chuck Bivona, who had worked at restaurants around the country and even done TV cooking competitions, all in service of his vision to open an Italian pasta shop, like the one his parents used to have, finally opened his shop after returning home and getting his footing with a few cooking events at Lodger.

Perhaps no one benefitted as much as the local high school kids who worked those hundreds of wild nights. They were paid a living wage and gained experience, vision, and access that is hard to come by. When school shut down during COVID, the school district used the tiny studio at Lodger as a hub to distribute hundreds of bagged lunches to kids who ordinarily depend on free lunch during the school day. During one of our many afternoon prep cooking, Johnson told me, “This only works if it’s part of the community.”

Undoubtedly, the place also became the darling of folks in the local arts community, a group that is changing the city’s face. But while other new restaurants hovered onto prominent street corners from another planet, hosting brightly lit parties while longtime locals watched from the windows, Lodger was discreet. It was part of the neighborhood. It was intentionally inclusive. Also, there was the bittersweet promise that it would only be around for a while, as the name Lodger implied.

To run a place like Lodger, with an open door to everyone, required risk and trust. As such, the place became a pure reflection not just of Johnson and his family but of the community. And it felt good being in that environment. It was the best place to eat in the area for five years without ever being a restaurant.

Now, the building has been sold, and the final dinners have been scheduled; Lodger has to vacate. I’m not sure what will happen with the space, but the locks will be changed, and the keys Johnson distributed to dozens of collaborators all over the city won’t fit the keyhole. But, if the place is to become something unrecognizable, I think it’s fitting that Lodger was the last tenant. Johnson honored all the ghosts, decorating the blue room with images of the original shopkeepers and using the sign, not of Lodger, but of the undertaker that once held his office there. And then there are all the shrines. I never asked Johnson about it, but he seemed to practice witchcraft or at least have a very participatory interest in Faustian mythology. As diners, glowing and invigorated, tasted spoonfuls of luscious eggplant and olives, they’d ask themselves, “Are we all under some spell? Is he charging these crystals and putting them in the food?” I’m not one for hokum, but I hope there is a spell to protect this place against future malintent. After the last dinners this past winter, when the door closed, dried maple leaves skittered over the bluestone and onto the threshold to preserve it again. Maybe this one room in a fast-changing city will keep its soul.

As for Johnson, we met in early August during a storm under a semi-permanent canvas round tent in his backyard a few blocks from the old Lodger. Sitting around a massive custom wooden table amid the rain, he said, “None of us have mentioned [Lodger] once since giving the keys back to the landlord.” Of those who started working at Lodger during their high school years in Newburgh, one is now an apprentice with a world-class chocolatier; another is a bookbinder and printer; another is off to medical school; another is preparing to go to college on an athletic scholarship.

Going forward, Johnson says, “the mission continues,” a mission he describes as “a collaborative creative enclave in proximity of food.” Johnson said. “It’s not Lodger 2.0; it’s called Anathémata, and I expect it will have the life of a mayfly.” While diners won’t have access to weekly dinners, groups of 10 to 14—which thus far have been assembled by a spice hunter, a troupe of Shakespearean actors, and a group of writers from Bard—gather for dinners or events. As before, those looking to collaborate with Johnson contact him through Instagram. The remaining team of now-veteran staff is the backbone of ongoing projects in the tent and far afield. They have hosted pop-ups in Kerhonkson and Kingston, including an ongoing Sunday residency at Flying Goose Tavern, while devising plans for destinations as far ranging as Cape Town and Berlin. The “traveling circus,” as Johnson’s son called it, it seems, will keep rolling along.